Here are some of the principles of trajectory sketching:

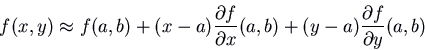

The linear approximation to a function of two variables ![]() near a

point

near a

point ![]() is

is

Example: Consider the system

![]() ,

,

![]() .

.

For an equilibrium point we need ![]() (i.e.

(i.e. ![]() or

or ![]() ) and

) and

![]() (i.e.

(i.e. ![]() or

or ![]() ). There are thus two equilibrium points:

). There are thus two equilibrium points:

![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Before classifying the equilibrium points, it's a good idea to draw the

isoclines for ![]() and

and ![]() . I'll plot the first in blue and the

second in green.

I indicate with arrows the direction field in each region and on the

isoclines. The intersections of the blue and green isoclines are the

equilibrium points.

. I'll plot the first in blue and the

second in green.

I indicate with arrows the direction field in each region and on the

isoclines. The intersections of the blue and green isoclines are the

equilibrium points.

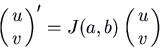

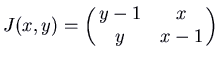

The Jacobian matrix is

. At the equilibrium point

. At the equilibrium point

![]() this is

this is

. That has

a double eigenvalue

. That has

a double eigenvalue ![]() , and two linearly independent eigenvectors.

Therefore the equilibrium point

, and two linearly independent eigenvectors.

Therefore the equilibrium point ![]() is a singular node, and is an

attractor.

is a singular node, and is an

attractor.

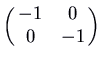

At the second equilibrium point ![]() the Jacobian matrix is

the Jacobian matrix is

. This has eigenvalues 1 and

. This has eigenvalues 1 and ![]() .

Therefore the equilibrium point

.

Therefore the equilibrium point ![]() is a saddle. The eigenvectors

are

is a saddle. The eigenvectors

are

![]() for 1 and

for 1 and

for

for ![]() . The picture below shows the phase plane with

some parts of trajectories near the two equilibrium points. Note that

the directions of these trajectories agree with the direction field

arrows from the previous picture.

. The picture below shows the phase plane with

some parts of trajectories near the two equilibrium points. Note that

the directions of these trajectories agree with the direction field

arrows from the previous picture.

Now we sketch some trajectories.

There are trajectories on the ![]() and

and ![]() axes (going inwards to the equilibrium

point at the origin), because

axes (going inwards to the equilibrium

point at the origin), because ![]() when

when ![]() and

and ![]() when

when ![]() .

Next it's a good idea to sketch the

trajectories coming out of and going in to the saddle point.

For example, one comes in to the saddle point from below and to the right.

We go backwards in time, following the arrows backward. These arrows

point up and left in the region

.

Next it's a good idea to sketch the

trajectories coming out of and going in to the saddle point.

For example, one comes in to the saddle point from below and to the right.

We go backwards in time, following the arrows backward. These arrows

point up and left in the region ![]() ,

, ![]() . The trajectory

must curve to avoid the trajectory on the positive

. The trajectory

must curve to avoid the trajectory on the positive ![]() axis. It is

presumably asymptotic to that axis. The trajectory coming out of the

saddle point down and to the left must continue down and to the left

until it ends at the equilibrium point

axis. It is

presumably asymptotic to that axis. The trajectory coming out of the

saddle point down and to the left must continue down and to the left

until it ends at the equilibrium point ![]() .

.

Finally, we draw some more trajectories, including at least one in each region.

Note that those trajectories that enter the equilibrium point at ![]() can do so at any angle.

can do so at any angle.

Our picture is symmetric about the line ![]() , because of the fact that the

system of equations remains the same if you interchange

, because of the fact that the

system of equations remains the same if you interchange ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The trajectories entering and leaving the saddle point are separatrices.

All trajectories below and to the left of the two trajectories entering

the saddle go to the equilibrium point ![]() as

as ![]() , while those

above and to the right go off to infinity asymptotic to the line

, while those

above and to the right go off to infinity asymptotic to the line ![]() .

Below and to the right of the trajectories leaving the saddle, everything

comes in from

infinity asymptotic to the positive

.

Below and to the right of the trajectories leaving the saddle, everything

comes in from

infinity asymptotic to the positive ![]() axis (as

axis (as ![]() ),

while above and to the left

of these everything comes in from infinity asymptotic to the positive

),

while above and to the left

of these everything comes in from infinity asymptotic to the positive ![]() axis.

axis.

As I mentioned, there are two exceptions to the rule that the phase portrait

near an equilibrium point can be classified by the

linearization at that equilibrium point. The first is where 0 is an

eigenvalue of the linearization (we didn't even look at the linear system

in that case!).

The second exception is where

the linearization is a centre. The linear system has periodic solutions,

corresponding to trajectories that are closed curves (ellipses). Imagine

starting at some point and following the direction field. After going

all the way around the equilibrium point, in the linear system you return

exactly to the point you started at. This is a very delicate matter,

and any nonlinear effect, even if very small, could spoil it. If in

the nonlinear system you come

back slightly farther away from the equilibrium point than where you started,

then your trajectory can not be a closed curve. The next time around, you

will be still farther away. The trajectory will spiral away from the

equilibrium point. If all trajectories

near the equilibrium point are like this, the equilibrium point is an unstable spiral.

On the other hand, if after one turn around the equilibrium point you are

slightly closer than where you started, your trajectory spirals inwards.

If all trajectories near the equilibrium point are like this, the equilibrium point

is a stable spiral (and an attractor).

Here are pictures of those two possibilities. The third possibility, of course,

is that you do come back exactly to the point where you started,

and it really is a centre.

One way to show that a centre of the linearized system is

still a centre in the nonlinear system is to find an equation for

the trajectories. If there is such an (implicit) equation ![]() where

where ![]() is a smooth function, not constant in any region,

and

is a smooth function, not constant in any region,

and ![]() an arbitrary constant, then the trajectories, which are level curves of

this function, can not be spirals but can be closed curves. This occurs

both in the predator-prey and pendulum systems.

an arbitrary constant, then the trajectories, which are level curves of

this function, can not be spirals but can be closed curves. This occurs

both in the predator-prey and pendulum systems.